Marceau, Marcel

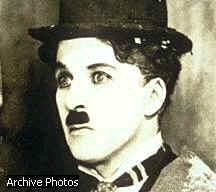

(1923- ), French mime, born in Strasbourg, considered to have almost

single-handedly revived the ancient art of pantomime. One of his first

opportunities to perform came shortly after World War II, when he

entertained French occupation troops in Germany. In 1946 he enrolled at

the School of Dramatic Arts in Paris, at which he studied with �tienne

Decroux. In 1947 he created his famous mime character Bip, a white-faced

clown clothed in culottes, a middy, and wearing a battered top hat. In a

great variety of poignant and comic sketches, Bip is beloved by

theatergoers around the world. Marceau's one-man show was probably the

outstanding success of the 1955-56 theatrical season in New York City, and

he has since toured the U.S. many times. He has also appeared frequently

on television.

Tati, Jacques

(1908-1982), French comic actor and motion-picture director, best known as

the clumsy, good-natured Monsieur Hulot, a character from his most

celebrated films. Tati was born Jacques Tatischeff in Le Pecq, near Paris,

into a Russian aristocratic family. He began his entertainment career as a

performer in cabarets and music halls, where he pantomimed popular sports

heroes.

Tati's first major film roles were in Sylvie et le

fantome (Sylvie and the Phantom, 1946) and Le diable au corps

(Devil in the Flesh, 1946), both by French director Claude

Autant-Lara. In 1947 Tati directed his own short comedy, L'�cole des

facteurs (The School for Postal Clerks), which he later expanded into

the highly successful Jour de f�te (The Big Day, 1949), a

parody of mechanization at the expense of individual dignity. Tati

introduced his bumbling alter ego, Monsieur Hulot, in Les vacances de

Monsieur Hulot (Mr. Hulot's Holiday, 1953), which starred Tati

himself in the title role. In this and subsequent films directed by and

starring Tati�including Mon oncle (My Uncle, 1958), Playtime

(1968), and Trafic (Traffic, 1971)�Mr. Hulot is invariably

baffled by the depersonalizing assaults of modern life. Tati's last film, Parade

(1974), was a tribute to the French pantomime tradition.

Tati was a determined perfectionist, often working with

limited budgets. As a result, he was able to complete relatively few films

in his lifetime, but they remain landmark screen comedies.

Game Involving Pantomime

Charades, riddles consisting of a word of two or more

syllables, which are to be guessed from the representation, by word of mouth

or by pantomime, of a meaning suggested by the separate syllables and then

by the entire word. Spoken or written charades may be verse or prose. The

British poet Winthrop Mackworth Praed was noted for his witty written

charades. The following is an example of the spoken charade.

My first is to ramble;

My next to retreat;

My whole oft enrages

In Summer's fierce heat.

Answer: Gadfly.

The acted charade consists of a pantomime in which the

various syllables of a word, or an entire word or phrase, are acted out. If

the answer to the charade is "football," the syllables foot

and ball are pantomimed. Pantomimic charades are a popular game at

parties in the United States and the United Kingdom. The participants are

generally divided into two competing groups, each group acting out a number

of charades that the other must guess. Charades reputedly originated in

France in the 18th century.

I INTRODUCTION

Musical

or Musical Comedy, theatrical production in which songs and choruses,

instrumental accompaniments and interludes, and often dance are integrated

into a dramatic plot. The genre was developed and refined in the United

States, particularly in the theaters along Broadway in New York City, during

the first half of the 20th century. The musical was influenced by a variety

of 19th-century theatrical forms, including operetta, comic opera (see

Opera), pantomime,

minstrel show, vaudeville, and burlesque.

II ORIGINS

The American musical has

its roots in a series of 18th- and early 19th-century theatrical productions

involving music. Of these, the best known is The Archers; or, The

Mountaineers of Switzerland, (1796), composed by Benjamin Carr, with a

libretto (the text of the musical) by William Dunlap. The Black Crook

(1866), which ran for 475 performances and combined melodrama with ballet,

is generally credited as being the first musical. In the late 19th century,

operettas from Vienna, Austria (composed by Johann Strauss, Jr., and Franz

Leh�r), London (by Sir Arthur Sullivan, with librettos by Sir William S.

Gilbert), and Paris (by Jacques Offenbach) were popular with Eastern urban

audiences. At the same time, revues (plotless programs of songs,

dances, and comedy sketches) abounded not only in theaters but also in some

upper-class saloons, such as the music hall operated in New York City by the

comedy team of Joe Weber and Lew Fields. The successful shows of another

comedy team, Ned Harrigan and Tony Hart, were also revues, but had

connecting dialogue and continuing characters. These in turn spawned the

musical shows of multitalented George M. Cohan, the first of which appeared

in 1901.

In the years before World

War I (1914-1918), several young operetta composers emigrated from Europe to

the United States. They included Victor Herbert, Rudolf Friml, and Sigmund

Romberg. Herbert's Naughty Marietta (1910), Friml's The Firefly

(1912), and Romberg's Maytime (1917) are representative of the new

genre these composers created: American operetta, with simple music and

librettos and memorable songs that were enduringly popular with the public.

III

THE MODERN MUSICAL

In 1914 composer Jerome

Kern began to produce a series of shows in which all the varied elements of

a musical were integrated. Produced in the intimate Princess Theatre in New

York City, Kern's musicals featured contemporary settings and events, in

contrast to operettas, which always took place in fantasy lands. In 1927

Kern provided the score for Show Boat, which had the first serious

libretto. It was also adapted from a successful novel, a technique that was

to proliferate in post-1940 musicals.

Gradually the old musical

formula began to change. Instead of complicated but light plots,

sophisticated lyrics and simplified librettos were introduced; underscoring

(music played as background to dialogue or movement) was added; and new

types of American music, such as jazz and blues, were utilized by composers.

In addition, singers began to learn how to act. In 1932 Of Thee I Sing

(1931) became the first musical to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize in drama. Its

creators, composer George Gershwin and lyricist Ira Gershwin, had succeeded

in intelligently satirizing contemporary political situations.

In the 1920s satire,

ideas, and wit had been elements of the intimate revue. These sophisticated

shows were important as testing grounds for the young composers and

lyricists who later helped develop the serious musical. One

composer-lyricist pair who started in the intimate revues, Richard Rodgers

and Lorenz Hart, wrote a show in 1940, Pal Joey, that had many of the

elements of the later musicals, including a book (the spoken dialogue

in the musical) with fully developed characters. But it was not a success

until its 1952 revival. In the meantime Rodgers, with Oscar Hammerstein II

as his new collaborator, had produced Oklahoma! (1943), which had

ballets, choreographed by Agnes de Mille, that were an integral part of the

plot. The role of the choreographer-director was eventually to become vastly

influential on the shape and substance of the American musical. Jerome

Robbins, Michael Kidd, Michael Bennett, and Bob Fosse are notable among the

skilled choreographers who went on to create important musicals, most

memorably Bennett's A Chorus Line (1975) and Fosse's Dancin'

(1978).

IV POST-WORLD

WAR II ERA

As these and other

innovations altered the conventions of musical theater, audiences came to

expect more variety and complexity in their shows. A host of inventive

composers and lyricists obliged. In 1949 Cole Porter, who had written

provocative songs with brilliant lyrics for many years, finally wrote a show

with an equally fine book: Kiss Me Kate. Rodgers and Hammerstein

followed Oklahoma! with Carousel (1945) and South Pacific

(1949). Irving Berlin, who had been writing hit songs since 1911, produced

the popular but somewhat old-fashioned Annie Get Your Gun (1946).

Frank Loesser provided both words and music for Guys and Dolls

(1950), with its raffish characters created by Damon Runyon. Brigadoon

(1947) was the first successful collaboration of composer Frederick Loewe

and book-and-lyric writer Alan Jay Lerner, who were later to contribute My

Fair Lady (1956), based on Pygmalion (1913) by British dramatist

George Bernard Shaw, and Camelot (1960).

In the 1950s a number of

composers gained prominence. Leonard Bernstein wrote the scores for Candide

(1956) and West Side Story (1957). The latter, a modern adaptation of

Romeo and Juliet, consisted mostly of dance and was heavily

underscored and greatly influential. Jule Styne wrote the music for Bells

Are Ringing (1956) and Gypsy (1959). In the 1960s and 1970s

composer Sheldon Harnick and lyricist Jerry Bock produced Fiddler on the

Roof (1964); composer John Kander and lyricist Fred Ebb collaborated on Cabaret

(1966); and Stephen Sondheim, who wrote the lyrics for West Side Story

and Gypsy, created the entire scores for a series of musicals,

including Company (1970), Follies (1971), A Little Night

Music (1973), and Sweeney Todd (1979). Many musicals were also

staged by black American companies, including The Wiz (1975), adapted

from the book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) by American writer L.

Frank Baum, and One Mo' Time (1979). Hair opened on Broadway

in 1968 and went on to affect world theater. Called a folk-rock musical, it

had a rambling, unfocused plot, and its lyrics, as performed, were often

unintelligible. But its youthful exuberance, ingenious theatricality, and

concentration on rock music produced many imitators, notably Godspell

and Jesus Christ Superstar (both 1971). The score for the latter was

the work of English composer Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber, who went on to write

the hits Evita (1978), based on the life of Argentine political

figure Eva Per�n; Cats (1981), based on verse by Anglo-American poet

T. S. Eliot; Song and Dance (1982); The Phantom of the Opera

(1988); and Sunset Boulevard (1994). The traditional La Cage aux

Folles (1983) by composer Jerry Herman and playwright Harvey Fierstein

and the innovative Sunday in the Park with George (1984), by Stephen

Sondheim, to a book by James Lapine, were also notable; for this work, a

dramatization of the life of French painter Georges Seurat, Sondheim and

Lapine shared the 1985 Pulitzer Prize for drama. In 1987 the musical

adaptation of the novel Les Mis�rables by French writer Victor Hugo

opened on Broadway to popular acclaim. Musicals of the 1990s include Miss

Saigon (1991); The Kiss of the Spider Woman (1993); Rent

(1996); Bring in 'da Noise, Bring in 'da Funk (1996); and Ragtime

(1998).

Contributed By:

Lehman Engel

Sign

Language

I INTRODUCTION

Sign

Language,

communication system using gestures that are interpreted visually. Many

people in deaf communities around the world use sign languages as their

primary means of communication. These communities include both deaf and

hearing people who converse in sign language. But for many deaf people, sign

language serves as their primary, or native, language, creating a strong

sense of social and cultural identity.

People who use sign language to communicate sometimes spell

out words, signing letters of the alphabet with their fingers. The American

Manual Alphabet is the fingerspelling system most commonly used in the

United States.

� Microsoft

Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

Sign language can also be

used as an alternative means of communication by hearing people. For

example, in the United States during the 19th century, groups of Native

Americans in the Plains who spoke different languages used a sign language

now known as Plains Indian Sign Talk to communicate with each other.

Languages can be conveyed

in different ways known as modalities. The most important modalities are

speech, writing, and sign. Modality should not be confused with language,

however. English and Navajo, for example, share a modality�speech�although

they are different languages. The same is true for sign languages. Even

though British Sign Language (BSL) and American Sign Language (ASL) share

the signed modality, they are two distinct languages. English, Navajo, BSL,

and ASL constitute four distinct languages.

Sign languages exhibit the same types of variation that

spoken languages do. For example, sign languages have dialects that vary

from region to region. In the United States, many African Americans in the

South who communicate through sign language use a variant of standard ASL,

just as many African Americans might communicate through their own

vernacular English in speech. In Switzerland, there are five geographic

dialects of Swiss German Sign Language with slight variations that derive

from regional schools for the deaf. In Dublin, Ireland, where boys and girls

attend different schools, the sign language used by deaf boys has a

distinctly different vocabulary from that used by deaf girls. Although girls

learn the boys� signs when they begin dating, after marriage women

continue to use the female signs with girls and women.

II SIGN

LANGUAGE AND DEAF EDUCATION

The first school for the

deaf, the Institut Royal des Sourds-Muets (Royal Institute for the Deaf and

Mute), was established in Paris during the 18th century. Teachers at the

institute taught in French Sign Language (FSL), a language already in use in

Paris and other parts of France.

In 1816 American educator Thomas Gallaudet traveled to Paris

to study the French method of deaf education at the institute. His interest

was prompted by the deaf daughter of a close friend who wished to go to

school. Gallaudet returned to the United States with a deaf teacher named

Laurent Clerc and together they established the first American school for

the deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817. They adapted the French signing

method for use in American classrooms. The merger of French signs with signs

in use by American deaf people formed what is now called American Sign

Language.

Opposition to teaching sign language in the classroom arose

at the end of the 19th century from educators who believed in teaching deaf

children to speak, a method known as oralism. Supporters of oralism proposed

that deaf people would be less isolated from the hearing community if they

learned to speak instead of sign. They also claimed that speech was a gift

from God and viewed sign language as an inferior system of communication. By

the beginning of the 20th century oralism had become the accepted method of

deaf education in both the United States and France. Schools for the deaf

promoted lip reading and speaking, often punishing children when they signed

among themselves.

In the 1960s American linguist William C. Stokoe pioneered

the modern linguistic study of sign language. By demonstrating that sign

languages were natural languages with distinct vocabularies and grammatical

structures, Stokoe�s work changed the way in which deaf educators viewed

oralism. Although American educators still taught lip reading and speaking,

during the 1970s and 1980s they began to bring the teaching of sign language

back into the classroom. In the 1990s U.S. educators remain divided on

whether and how to teach ASL to deaf children, and the extent to which sign

language is used in the classroom varies from school to school.

Although exact numbers are unavailable, estimates of the

number of deaf people in the United States and Canada who use American Sign

Language (ASL) as their primary language range from 100,000 to 500,000.

III

CHARACTERISTICS OF SIGN

LANGUAGE

Linguists have found that

sign languages and spoken languages share many features. Like spoken

languages, which use units of sounds to produce words, sign languages use

units of form. These units are composed of four basic hand forms: hand

shape, such as an open hand or closed fist; hand location, such as on the

middle of the forehead or in front of the chest; hand movement, such as

upward or downward; and hand orientation, such as the palm facing up or out.

In spoken languages units of sound combine to make meaning.

Separately, b, e, and t have no meaning. However, together

they form the word bet. Sign languages contain units of form that by

themselves hold no meaning, but when combined create a word. Spoken

languages and sign languages differ in the way these units combine to make

words, however. In spoken languages units of sound and meaning are combined

sequentially. In sign languages, units of form and meaning are typically

combined simultaneously.

IV AMERICAN

SIGN LANGUAGE

In ASL signs follow a

certain order, just as words do in spoken English. However, in ASL one sign

can express meaning that would necessitate the use of several words in

speech. For example, the words in the statement "I stared at it for a

long time" each contain a unit of meaning. In ASL, this same sentence

would be expressed as a single sign. The signer forms "look at" by

making a V under the eyes with the first and middle fingers of the right

hand. The hand moves out toward the object being looked at, repeatedly

tracing an oval to indicate "over a long time." To express the

adverb "intently" the signer squints the eyes and purses the lips.

(To purse the lips is like saying mmmm; pull back and tighten the

lips with the lips closed.) Although the English words used to describe the

ASL signs are written out in order, in sign language a person forms the

signs "look at,""long time," and "intently" at

the same time.

ASL has a rich system for modifying the meaning of signs.

Verbs such as "look at" can be changed to indicate that the

activity takes place without interruption, repeatedly, or over a long time.

The adjective "sick," for example, is formed by placing the right

middle finger on the forehead and the left middle finger on the stomach. By

forming the sign "sick" and repeatedly moving the left hand in a

circle, the signer can indicate that someone is characteristically or always

sick.

Facial grammar, such as raised eyebrows, also can modify

meaning. For example, a signer can make the statement "He is

smart" by forming the ASL sign for "smart"�placing the

middle finger at the forehead�and then quickly pointing it outward as if

toward another person to indicate "he." To pose the question

"Is he smart?" the signer accompanies this sign with raised

eyebrows and a slightly tilted head.

V OTHER

SIGNING SYSTEMS

People who sign sometimes

use fingerspelling to represent letters of the alphabet. In some sign

languages, including ASL, fingerspelling serves as a way to borrow words

from spoken language. A deaf person might, for example, choose to

fingerspell "d-o-g" for "dog" instead of using a sign.

Several types of fingerspelling systems exist. FSL and ASL use a one-handed

system, whereas BSL has a two-handed system.

In an effort to teach deaf children the spoken and written

language of the hearing community, educators of deaf children often use

invented sign systems in addition to the primary sign language. Examples of

such systems in the United States include Signing Exact English, Seeing

Essential English, and Cued Speech. These systems often mix ASL signs with

English word order and grammar. Typically, they incorporate a sign from ASL

to represent the base or stem of a spoken English word. To this they add

various invented signs to form suffixes (for example, the -ness at

the end of kindness), prefixes (for example, the pre- at the

beginning of premature), and other parts of words. In this way, the

signed English word prearrangements might consist of a base sign for

"arrange" together with invented signs for the prefix pre-

and the suffixes -ment and -s.

In Signed Exact English, a fingerspelled letter is sometimes

used in conjunction with a sign in a process called initialization. For

example, by fingerspelling "f" or "e" with the base sign

"money" (a two-handed gesture in which the upturned right hand,

grasping some imaginary bills, is repeatedly brought down onto the upturned

left palm) a signer can differentiate between the English words finance

and economics.

Linguists still have much to learn about the world�s sign

languages. What has become clear is that hundreds, if not thousands, of sign

languages exist around the world.

Contributed By:

Sherman Wilcox

Movie

Children of Paradise

,

French motion picture about several romances among theatrical people in

19th-century Paris. Released in 1945, the film was made during the German

occupation of France and contains references to the work of the French

Resistance movement. After the mime Baptiste (Jean-Louis Barrault) saves a

young girl (Arletty) from being accused of theft, the girl feels attracted

to Baptiste but falls in love with another man. Years later, when both of

them are involved in other relationships, they meet and fall in love again.

Alternate Title

Les Enfants du Paradis

Director

Marcel Carn�

Cast

Arletty (Garance)

Jean-Louis Barrault (Baptiste Debureau)

Pierre Brasseur (Frederick Lemaitre)

Marcel Herrand (Lacenaire)

Pierre Renoir (Jericho)

Maria Casar�s (Natalie)

Etienne Decroux (Anselme Debureau)

Fabien Loris (Avril)

Leon Larive (Stage doorman, "Funambules")

Pierre Palov (Stage manager, "Funambules")

Marcel Peres (Director, "Funambules")

Albert Remy (Scarpia Barrigni)

Jeanne Marken (Madame Hermine)

Gaston Modot (Fil de Sole)

Louis Salou (Count Edward de Monteray)

Jacques Castelot (George)

Jean Gold (Second dandy)

Guy Favieres (Debt collector)

Paul Frankeur (Police inspector)

Lucienne Vigier (First pretty girl)

Cynette Quero (Second pretty girl)

Gustave Hamilton (Stage doorman, "Grand Theatre")

Rognoni (Director, "Grand Theatre")

Auguste Boverio (First author)

Paul Demange (Second author)

Jean Diener (Third author)

Louis Florencie (Police officer)

Marcelle Monthil (Marie)

Robert Dhery (Celestin)

Lucien Walter (Ticket seller)

Jean-Pierre Delmon (Little Baptiste)

Raphael Patorni (Another dandy)

Jean Lanier (Iago)

Habib Benglia (Arab attendant)

Petit, Roland (1924- ), French dancer and

choreographer, known for his inventive and theatrical ballets. He was born

in Villemomble, near Paris, and trained at the ballet school of the Paris

Op�ra. A charismatic dancer, Petit organized several ballet troupes,

including the Ballets de Paris (1948-1958), and served as the artistic

director of the Ballets de Marseille beginning in 1972.

Petit's choreography, noted for its highly dramatic and

sophisticated style, borrowed freely from modern dance, classical ballet,

pantomime,

and the music hall. His notable ballets include Le jeune homme et la mort

(The Young Man and Death, 1946), Les forains (The Traveling Players,

1948), Carmen (1949), Le loup (the Wolf, 1953), Notre-Dame

de Paris (1965), Paradise Lost (1967), and Les amours de

Frantz (The Loves of Frantz, 1981). He also choreographed several motion

pictures and music hall revues. In 1954 he married the star of many of his

productions, Ren�e Jeanmaire. In 1993 Petit published his memoirs, J'ai

dans� sur les flots (I Danced on the Waves).

Kreutzberg, Harald

(1902-1968), German modern dancer and choreographer, known for his solo

performances. Born in Reichenberg, Austria-Hungary (now Liberec, Czech

Republic), Kreutzberg studied ballet at the Dresden Ballet School in

Dresden, Germany. He studied modern dance with Hungarian dancer and movement

theorist Rudolf von Laban and with German modern dance choreographer Mary

Wigman. In 1922 Kreutzberg joined the Hannover Ballet in Hannover, Germany.

He later became a major leader of modern dance in Germany and toured Europe

and North America with his dance partner Yvonne Georgi.

Between 1932 and 1934 Kreutzberg toured in the United States

and in East Asia in collaboration with innovative American ballet

choreographer Ruth Page. Thereafter he mostly performed alone, creating

solos that combined dance with dramatic devices such as mime (see

Pantomime) and inventive costuming. His shaven head became his trademark. In

1955 Kreutzberg opened a dance school in Bern, Switzerland. He retired from

performing in 1959, after which time he concentrated on teaching and

choreographing for other dancers.

Kathak north Indian style of classical dance,

characterized by rhythmic footwork danced under the weight of more than 100

ankle bells, spectacular spins, and the dramatic representation of themes

from Persian and Urdu poetry alongside those of Hindu mythology. Kathak

arose from the fusion of Hindu and Muslim cultures that took place during

the Mughal period (1526-1761). More than any other South Asian dance form,

kathak expresses the aesthetic principles of Islamic culture. The influence

of kathak is also visible in the Spanish flamenco tradition.

The origins of the kathak style lie in the traditional

recounting of Hindu myths by Brahmin priests called kathiks, who used

mime and gesture for dramatic effect. Gradually, the storytelling became

more stylized and evolved into a dance form. With the arrival in northern

India of the Mughals, kathak was taken into the royal courts and developed

into a sophisticated art form; through the patronage of the Mughal rulers,

kathak took its current form. The emphasis of the dance moved from the

religious to the aesthetic. In accordance with the aesthetics of Islamic

culture, abhinaya (the use of mime and gesture) became more subtle,

with emphasis placed on the performer's ability to express a theme in many

different ways and with infinite nuances.

There are two main schools, or gharanas, of kathak

dance, both of which are named after cities in northern India and both of

which expanded under the patronage of regional princes. The Lucknow gharana

developed a style of kathak that is characterized by precise, finely

detailed movements and an emphasis on the exposition of thumri, a

semiclassical style of love song. The Jaipur gharana required a mastery of

complicated pure dance patterns. Nowadays, however, performers present a

blend of kathak based on the styles of both gharanas.

A traditional kathak performance features a solo dancer on a

stage, surrounded on all sides by the audience. The repertoire includes amad

(the dramatic entrance of the dancer on stage); thaat (a slow,

graceful section); tukra, tora, and paran (improvised dance

compositions); parhant (rhythmic light steps), and tatkar

(footwork). Male dancers perform in Persian costume of wide skirts and round

caps, while female dancers wear a traditional Indian garment called a sari.

Developments in this century include the use of kathak in large-scale dance

dramas, pioneered by Pandit Birju Maharaj, the present leader of the Lucknow

gharana. In recent years, choreographers such as Kumudini Lakhia and

British-based Nahid Sidiqui have explored the vocabulary of kathak to

express contemporary themes. Other dancers have created performances showing

the links between kathak and European dance traditions such as flamenco and

Romani (Gypsy) dance. See also Indian Dance.

The southern Indian kathakali is a dance drama that

dates from the 17th century and is rooted in Hindu mythology. Male dancers

perform kathakali at religious ceremonies and in exhibitions for

tourists. The rhythmic cycle and melodic scale of traditional southern

Indian music direct the dancer�s movements. This performer wears

ceremonial makeup and dress that includes a large, circular headdress made

of wood.

Photo Researchers, Inc./"Kathakali Dance

Theater" from Ritual Music and Theater of Kerala (Cat.# Le Chant du

Monde LDX 274 010) (p)1989 Le Chant du Monde. All rights reserved.

Kathakali, spectacular dance-drama form of the southern

Indian region of Kerala, characterized by its complex language of mime and

highly stylized and colorful makeup that resemble masks.

A kathakali performance includes few props since the details

of a scene are described in mime. Stories involve heroes, villains, gods,

and demons, in addition to more subtle characterizations of those who commit

evil deeds yet retain a streak of valor. These personality traits are all

indicated by complex makeup, which can take up to three hours to apply and

which highlights facial expressions, a vital aspect of the art. The faces of

gods, heroes, and kings are always painted green with ridges of white rice

paste around the edges, while demons have red beards, white mustaches, and

knobs on their noses. All male dancers attach 7.5-cm (3-in) silver

fingernails on their left hands and put the juice of a crushed seed in their

eyes, causing them to appear red. Female dancers use simpler costumes and

makeup. The six-year training required for a kathakali dancer is arduous,

and the regular oil massages, included in training to promote turnout of the

legs, can be painful. The dance is athletic in nature, with dramatic leaps.

Costumes are colorful and include heavily decorated headdresses associated

with the parts played and voluminous white skirts enabling freedom of

movement. Apart from the occasional grunt from a demon character, the

dancers remain silent, enacting the story in mime

that is interspersed with sequences of pure dance. Performances

traditionally begin after dusk and end with sunrise, although individual

scenes are now often put together as an evening performance for modern,

urban audiences. The accompanying verses are rendered by two singers at the

back of the stage, and musical accompaniment is provided by cymbals, gong,

and drums called chenda and maddalam.

Originally an exclusively male art form, women are now

actively involved in kathakali as both performers and teachers. While the

pure dance elements require great skill, the quality of the performance is

ultimately judged by the dancer's interpretation of the role in mime. With a

complex system of 24 primary hand gestures (mudras), over 800

descriptive and symbolic meanings can be conveyed. Using regional

interpretations of the classic Hindu epics, the verses themselves are of

great interest in their sometimes unorthodox and challenging perceptions of

traditional Hindu belief.

Kathakali derives from both a rich folk culture and the

religious plays traditionally performed in temples. It developed more

specifically from ramanattam, a masque-like form involving music,

dance, and drama, which evolved in the 17th century as an effective vehicle

for the plays of the raja (prince) of Kottarakara. These plays were written

in the regional language of Malayalam, making them more accessible to a

wider audience than works in classical Sanskrit, a language known only by

the upper castes. The repertoire included themes from Hindu literature such

as the incarnation of the god Vishnu as Prince Rama in the Ramayana

and the territorial dispute between two noble families in the Mahabharata.

The art form, which became widely popular through royal patronage, soon

evolved the highly sophisticated features of a classical dance style. In the

18th century kathakali became a theater for people of all castes, with

performances held outside the temples. During the British rule of India

(1885-1947), kathakali suffered a serious decline. The current vigorous

revival results from efforts in the 1930s of the poet Vallathol, who was

largely responsible for its reestablishment, especially through his founding

of the major dance school of Kalamandalam, in Cheruthuruthi, a city in

southern India.